Summary

The [Israeli] soldiers came and told us to leave. No one told us where to go, just to get out of the camp. My fear is that what happened in 1948 will happen to us here. I have an inner belief that we won’t be able to come back ever.

– Nadim M., displaced from Tulkarem refugee camp, March 26, 2025

Nadim M., a pseudonym for a 60-year-old father of four, was forced to flee Tulkarem refugee camp in the West Bank of the Occupied Palestinian Territory in January 2025 when Israeli military forces raided the camp and stormed his home. He told Human Rights Watch that Israeli soldiers restrained him with zip ties, searched his property, and then ordered him and his family to leave, warning them that if they turned to go to the left or to the right they would be targeted by Israeli snipers who were deployed in high places nearby. With no clear destination and no information about available shelters or humanitarian assistance, Nadim M. and his family found refuge in a local mosque that had opened its doors to displaced residents from the camp.

On January 21, just two days after a temporary ceasefire was announced between Israel and Palestinian armed groups in Gaza, the Israeli military launched “Operation Iron Wall,” a large-scale operation in the West Bank that also involved Shin Bet, Israel’s security agency, and Border Police. Senior officials claimed the operation targeted militants in refugee camps in the northern West Bank governorates of Jenin and Tulkarem.

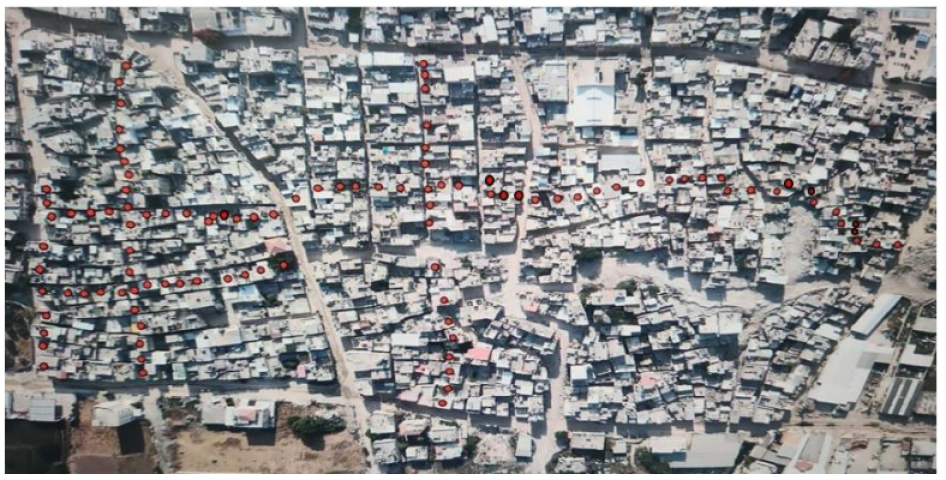

The operation emptied the camps in Jenin, Tulkarem, and Nur Shams of virtually all its residents, making it the largest displacement of Palestinians in the West Bank in one operation since the 1967 war. Ten months later, the camps remain empty with approximately 32,000 residents displaced. Since then, the Israeli military has demolished 850 homes and other buildings across all three camps. Nadim M. and his family have not returned to their home and have been struggling to live elsewhere in the West Bank.

This report examines the Israeli government’s conduct of Operation Iron Wall from its start in January 2025 through July 2025, and the resulting mass displacement of Palestinians from three refugee camps in the northern West Bank. Human Rights Watch found that Israeli forces committed forcible displacement in violation of the law of occupation under international humanitarian law that amount to war crimes. Human Rights Watch also found that Israeli forces committed the forcible transfer of population and other inhumane acts as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population, which are crimes against humanity under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. Israel’s actions also violated international human rights law, which remains in effect in the West Bank.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ), in its Advisory Opinion of October 22, 2025 on the obligations of Israel in relation to the Occupied Palestinian Territory, stated that the court “cannot fail to observe that Israel’s conduct in the Occupied Palestinian Territory raises serious concerns in light of its obligations under international humanitarian law and international human rights law … Thus, the Court reaffirms that Israel remains bound by these obligations and is required to comply with them.”[1]

Human Rights Watch between March and August 2025 interviewed in person and by phone 31 displaced Palestinians from the Jenin, Tulkarem, and Nur Shams refugee camps, and analyzed and verified open-source information and satellite imagery.

In the months prior to Operation Iron Wall, low-level clashes took place between Israeli security forces and Palestinian fighters in Jenin, Tulkarem, and Nur Shams refugee camps. There were also small-scale clashes in the immediate days leading up to and during the operation in each of the three refugee camps.

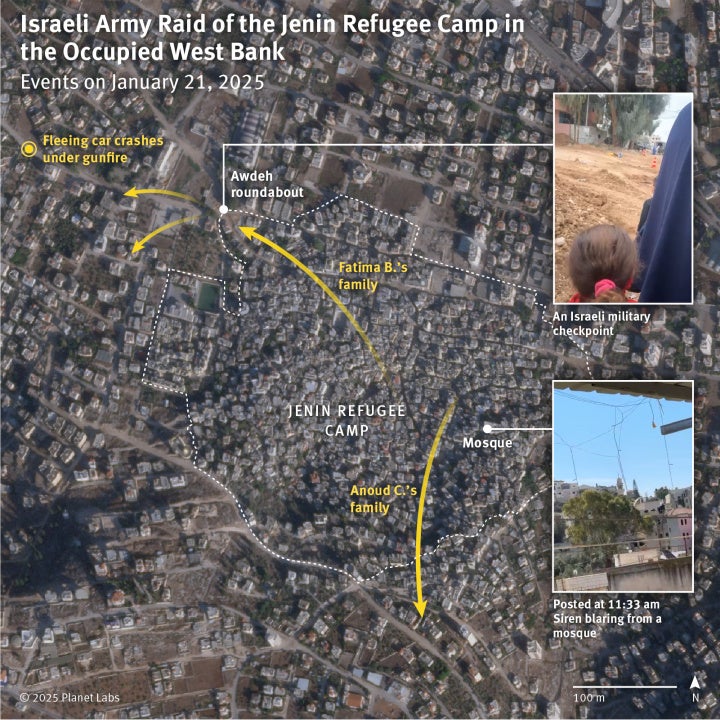

On January 21, Israeli forces carried out a massive raid on Jenin refugee camp, deploying Apache attack helicopters, drones, bulldozers, and armored vehicles to support hundreds of ground troops. Israeli soldiers forced residents from their homes amid active military operations. Residents who spoke to Human Rights Watch said they saw bulldozers demolishing roads and buildings as they were being expelled. Similar operations took place in Tulkarem refugee camp on January 27 and in nearby Nur Shams camp on February 9, following the same pattern of displacement and destruction.

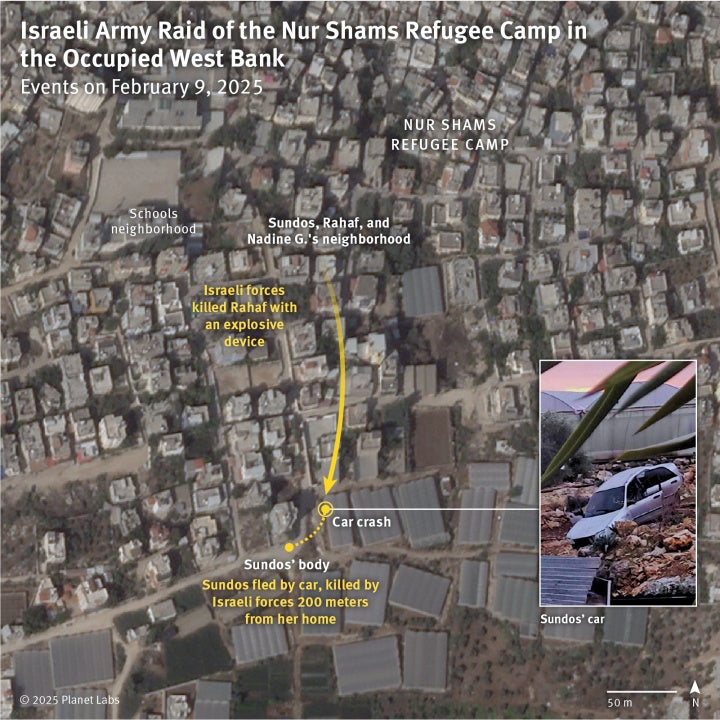

Witnesses said soldiers moved systematically through the camps, storming homes, ransacking properties, interrogating residents, and eventually forcing families out. One woman from Nur Shams said that she, her husband, and their 14-year-old daughter waited in terror inside their home and watched as Israeli soldiers used heavy machinery to destroy their garden wall, before ordering the family to leave their home and exit the camp. During the raid of Nur Shams camp on February 9, Israeli forces detonated an explosive device at the entrance of a family home, blasting the door open and killing 21-year-old Rahaf al-Ashqar and injuring her father.

Under article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, Israel, as the occupying power in the West Bank, is prohibited from displacing the population it is obliged to protect except temporarily in exceptional circumstances – namely, when evacuation is required for imperative military reasons or to ensure the safety of the civilian population. Even if one or both conditions are met, international humanitarian law strictly regulates how such evacuations must be carried out. The warring party must evacuate people safely, give them access to food, water, and proper accommodation, and allow them to return once the hostilities in that area have ended.

Displacements that do not meet these conditions are violations of international law and, if committed with criminal intent, are war crimes. When forced displacement is committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack on a civilian population, thus reflecting state or organizational policy, it can constitute a crime against humanity. These actions may also be considered “ethnic cleansing,” a non-legal term used to describe a policy to remove an ethnic or religious group from particular areas “by violent and terror-inspiring means.”

In all three camp raids, the Israeli military failed to take meaningful steps to ensure the safe and dignified evacuation of civilians. Instead, they issued abrupt orders to leave – either given by soldiers on the ground or broadcast via loudspeakers mounted on drones.

All the residents who spoke to Human Rights Watch described the humiliation and fear of being forcibly removed from their homes, unable to gather their belongings and uncertain if or when they would be allowed to return. In one case, Israeli soldiers in Tulkarem refugee camp prevented a man who uses a wheelchair from taking his more functional electric wheelchair. In the brief minutes people were given to leave, some residents said they only managed to take their immediate belongings or just the clothes on their back.

The Israeli military failed to provide camp residents with timely, consistent, or clear instructions on how to safely evacuate. In Jenin refugee camp, Israeli soldiers or orders delivered through drones told residents to exit through one point – the nearby Awdeh roundabout – where the military set up a makeshift checkpoint. In Tulkarem and Nur Shams camps, no designated exit routes were provided; instead, residents received varying instructions based on their location within the camps. Residents described fleeing under the watch of heavily armed soldiers, drones flying overhead apparently tracking their movements, and witnessing the widespread destruction of their homes while they fled.

Human Rights Watch found that during the repeated – and unlawful – displacement of Palestinians from their homes and places of refuge in Gaza since October 2023, Israeli authorities created a complex evacuation system and the designation of so-called “safe zones” for civilians. Despite these measures, Israeli forces unnecessarily put displaced people in harm’s way, which amounted to the war crime of forced displacement and crimes against humanity. By comparison, the Israeli forces that emptied the three West Bank refugee camps of their inhabitants in early 2025 did not even make such efforts.

The Israeli military provided no shelter or humanitarian assistance to displaced camp residents. Once forced out of the camps, people were left to fend for themselves. Many sought shelter wherever they could, crowding into the homes of relatives or friends, or turning to mosques, schools, and local charities. A July 2025 Médecins Sans Frontières report on the West Bank found that displacement-affected communities face growing instability and unmet needs, such as access to healthcare and regular food and water.

The Israeli authorities also did not take into account the needs of people with disabilities, many of whom were unable to leave without assistance and who struggled to navigate the bulldozed streets and find accessible shelter.

When the Israeli government launched Operation Iron Wall, it announced its intention to eliminate what Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu referred to as “terrorist elements.”

Prior to publication, on October 15, 2025, Human Rights Watch wrote to the Israeli military with an overview of this report’s preliminary findings and a list of questions relating to its research. The IDF International Press Desk responded by email on October 29, 2025, and this response is reflected in the report and reprinted in full as an appendix. The Israeli military confirmed their involvement in Operation Iron Wall, and said:

The operation was based on the understanding that terrorists exploit the terrain and the densely built environment of the camps, which restricts the IDF’s freedom of action. And that Hamas plants explosive devices in houses, civilian infrastructure, and along traffic routes in order to detonate them, thus endangering the lives of security forces and local residents.

The response included a links to photographs and videos depicting weapons allegedly found in civilian homes in the refugee camps and clips showing alleged fighting between the Israeli military and Palestinian fighters in the camps.

The Israeli military did not explain why the displacement of the entire population of all three camps was necessary to achieve its aims, nor whether alternatives had been considered. Rather, it stated that the “IDF has had to operate for an extended period of time, as required by operational needs and the circumstances on the ground.” The response did not answer Human Rights Watch’s questions about whether Israeli authorities had attempted to provide food, shelter, and access to medical services for the civilian population it had displaced, as required under international humanitarian law.

Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention only permits the displacement of civilians for the security of the population in an area or for imperative military reasons. The Israeli operations actually undermined the security of civilians affected and for displacement to qualify as a military imperative, it must be so essential that its failure would jeopardize an overall military objective.

It was not sufficient for the Israeli military to seek to justify wholescale civilian displacement solely on the basis of possible Palestinian fighters, weapons or installations in the refugee camps. Under the Fourth Geneva Convention, the occupying power needs to demonstrate that evacuating civilians was the only viable means it had at that moment to achieve its military aim. However, even had the government demonstrated this, it would also need to show that it had safely evacuated the population, provided them food and shelter, and ensured their return as soon as hostilities in the area ended.

Since the raids and forced displacement, Israeli authorities have repeatedly and uniformly denied camp residents the right to return to the camps, even though there are no active military operations taking place in the vicinity. Israeli soldiers have fired upon people trying to reach their homes, while only very few whose homes have been slated for demolition have been permitted a short window to return to collect essential belongings. The Israeli military has bulldozed and razed and cleared spaces for what appear to be bigger and wider access routes inside the camps and have blocked all entrances with earth mounds and barriers. In addition, Israeli soldiers have taken up positions inside the camps, where Israeli flags hang from buildings.

Within six months after the start of Operation Iron Wall, more than 850 buildings were destroyed or sustained heavy damage across all three camps, based on Human Rights Watch’s analysis of satellite imagery. A report by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) found that all three camps showed widespread destruction and the presence of Israeli military vehicles, roadblocks, bulldozers, and excavators.

In response to Human Rights Watch’s questions about the extensive destruction in the camps, the Israeli authorities said they were acting “to reshape and stabilize the area,” and that “an inseparable part of this effort is the opening of new access routes inside the camps, which requires the demolition of rows of buildings.” While the response said that “a public notice was issued before the demolitions,” authorities did not comment on Human Rights Watch’s findings that many buildings across all three camps were demolished without corresponding demolition orders. The Israeli military did not answer questions as to whether and when the residents of the three camps would be allowed to return to their homes.

In additional to international humanitarian law, the right of return is upheld in various human rights conventions and has been affirmed for Palestinian refugees through United Nations General Assembly resolutions dating back to 1948 and reaffirmed since then. Palestinians from Jenin, Tulkarem, and Nur Shams refugee camps are largely refugees – those who were expelled or forced to flee their homes during the events surrounding Israel’s creation in 1948 in what Palestinians refer to as the Nakba (“Catastrophe” in Arabic) and their descendants.

Displacing some 32,000 Palestinians, descendants of those who were expelled and became refugees nearly 80 years ago, has enormous consequences. Every camp resident who spoke to Human Rights Watch said they believed Israel was trying to eliminate the “refugee question” by removing them from the camps and destroying the camps, and, in doing so, eliminate their broader right of return to their original homes and land in what is now the state of Israel.

This forced displacement reflects the broader pattern of ongoing rights violations by Israeli authorities against the Palestinian population, including the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution. Since the start of Operation Iron Wall, Israeli authorities have not spoken of the camp residents’ returning to their homes, nor did the authorities, in their October 29 response to questions from Human Rights Watch, address when they would allow Palestinians to return to the refugee camps. Instead, Minister in the Defense Ministry Bezalel Smotrich, who sits on the security cabinet and also serves as Minister of Finance, said if the camp residents “continue their acts of ‘terrorism,’” the camps “will be uninhabitable ruins,” and that “[t]heir residents will be forced to migrate and seek a new life in other countries.”

The raids were carried out against a backdrop of increasing repression against Palestinians in the West Bank in recent years that escalated following the October 7, 2023, Hamas-led attacks by Palestinian armed groups on Israel. Since then, Israeli forces’ killings of nearly 1,000 Palestinians in the West Bank, use of administrative detention without charge or trial, and expansion of illegal settlements reached years-long highs, while state-backed settler violence, home demolitions and ill-treatment and torture of Palestinian detainees have also increased.

Israeli authorities have also escalated their longstanding campaign to undermine the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), the UN aid agency established in 1949 for Palestinian refugees in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. In early 2025, laws passed by the Knesset, the Israeli parliament, to block UNRWA from operating in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory came into effect. Since then, Israeli authorities have prevented UNRWA’s international staff from entering Gaza, and blocked UNRWA, which had been the largest assistance provider, from distributing aid in Gaza. They also issued closure orders for UNRWA-operated schools in East Jerusalem, keeping them from opening in September 2025 to the detriment of nearly 800 children, some of whom have been unable to enroll elsewhere.

In its October 22 advisory decision, the ICJ found that “to the extent that Israel does not itself fulfil the obligations” under the Fourth Geneva Convention to provide for the occupied population, “leaving that responsibility to the United Nations acting through UNRWA, … Israel is under the same positive and negative obligations to support and not to restrict the activities of those entities.”[2]

The Israeli military actions to permanently alter the camps months after taking control and presumably long since any military operation to root out “terrorist elements” demonstrates an intention to go beyond what is militarily necessary by carrying out systematic destruction without an evident military threat. The extensive destruction of civilian property not lawfully justified by military necessity is considered to be “wanton destruction” in violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention and those responsible should be prosecuted for war crimes.

Human Rights Watch has verified demolition orders related to the destruction of homes and other buildings across all three camps authorized by Maj. Gen. Abraham “Avi” Bluth, commander of the Central Command, and that reflect statements from the highest levels of the Israeli government. Bluth has publicly stated an intention to “reshape” the camps. Human Rights Watch’s satellite imagery-based analysis also shows large-scale destruction or heavy damage to buildings without a corresponding demolition order.

Beyond the immediate military action taken at the refugee camps, senior officials in the Israeli government have called for the displacement of camp populations for prolonged periods as a policy goal. “We will not return to the reality that was in the past,” said Minister of Defense Israel Katz in February 2025. “We will continue to clear refugee camps.”

Katz has furthermore called for permanent removal of the populations of the emptied camps, saying in February 2025, “I have instructed the IDF to prepare for a prolonged stay in the camps that have been cleared for the coming year – and not to allow residents to return and terrorism to grow again.” This statement, taken together with the Israeli authorities’ response to Human Rights Watch that referred to “reshaping” the camps and demolishing homes and other buildings without referencing residents’ returning, indicates an unlawful intent to prevent the return to the camps even after the end of hostilities in the area as required by international humanitarian law.

As the occupying power in the West Bank, the Israeli government remains responsible for ensuring food and health care of the population “[t]o the fullest extent of the means available to it” under articles 55 and 56 of the Fourth Geneva Convention. Since early 2025, the Israeli military has apparently done nothing for the populations forced out of the camps. Data from OCHA shows that the Israeli authorities increased movement restrictions across the occupied West Bank, making it harder for humanitarian agencies to reach them.

Human Rights Watch found that the Israeli military’s displacement of the populations in the West Bank refugee camps in early 2025 were carried out in violation of international humanitarian and human rights law, and amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity. The Israeli military intentionally and purposefully displaced thousands of Palestinians in the refugee camps by means of forced displacement. It forcibly expelled people from their homes using violence and the fear of violence and at times used lethal force. The Israeli army did not provide safe routes out of the camps and just directed people to leave while at the same time apparently deploying snipers and immediately commencing the destruction of homes.

The organized, forced displacement of Palestinians in the refugee camps has removed nearly the entire Palestinian population from these areas that for decades and generations has been their home. This is evident in areas that have been razed, extended, and cleared for new and widened military access roads. These areas are now fully emptied of Palestinians, and the Israeli government has given no indication that the residents of the camps would be allowed to return.

Forced displacement can amount to a crime against humanity when it is committed as a part of a widespread or systematic “attack directed against a civilian population,” which means the multiple commission of such crimes committed pursuant to a state or organizational policy. The crime against humanity of forced displacement is defined under the Rome Statute as deportation or forcible transfer, meaning forced displacement of the persons concerned by expulsion or other coercive acts from the area in which they are lawfully present, outside the limited exceptions permitted under international law.

By expelling tens of thousands of Palestinians from refugee camps, dictating the manner of their displacement, and preventing their return for months after military operations ended, Israeli forces have carried out widespread, systematic, and intentional forced displacement that amounts to crimes against humanity. The actions by Israeli authorities to remove Palestinians from the refugee camps by violent means also amounts to “ethnic cleansing,” a non-legal term to describe the actions of one ethnic or religious group against another ethnic or religious group.

Individuals responsible for the commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity can face criminal liability not only in the domestic courts of the country where the crimes took place, but also in international courts and tribunals, as well as in other countries’ courts under the principle of universal jurisdiction in accordance with national laws. Under the principle of command or superior responsibility, military and civilian officials up to the top of the chain of command can also be held criminally responsible for crimes committed by their subordinates. Command responsibility attaches when superiors knew or should have known that their subordinates were committing such crimes but failed to take reasonable measures to prevent the crimes or punish those responsible.

Human Rights Watch’s research indicates that Maj. Gen. Avi Bluth, as the commander of Central Command in charge of military operations in the West Bank, should be investigated for individual criminal responsibility for war crimes and crimes against humanity, including as a matter of command responsibility , concerning the expulsion, some 32,000 people from the refugee camps of Jenin, Tulkarem, and Nur Shams.

Maj. Gen. Avi Bluth reports to the Chief of the General Staff of the Israeli army. Lt. Gen. Herzi Halevi held this role until March 5, 2025, at which time Lt. Gen. Eyal Zamir took over. Halevi and Zamir should also be investigated for individual criminal responsibility in these crimes as a matter of command responsibility.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Minister of Defense Israel Katz, and Minister in the Defense Ministry Bezalel Smotrich, who sits on the security cabinet and also serves as Minister of Finance, should also be investigated for individual criminal responsibility, including as a matter of command responsibility, for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The ICC Office of the Prosecutor and domestic judicial authorities under the principle of universal jurisdiction should investigate those Israeli officials credibly implicated in war crimes and crimes against humanity in the West Bank, including as a matter of command responsibility.

Governments should impose targeted sanctions against Bluth, Smotrich, Katz, Netanyahu, and other Israeli officials implicated in ongoing grave abuses in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. They should take other actions to press Israeli authorities to end their repressive policies, including imposing an arms embargo, suspending preferential trade agreements with Israel, banning trade with illegal West Bank settlements, and committing to enforce the ICC’s arrest warrants.

Governments should adhere to the full set of obligations set out in the landmark July 2024 ICJ advisory opinion on Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian Territory. The ruling found Israel’s decades-long occupation to be unlawful and in breach of the Palestinians’ right to self-determination. The court found that Israel is responsible for apartheid and other serious abuses against the Palestinians, that its settlements are illegal and should be dismantled, and that the Palestinians are entitled to reparations. The court set out numerous obligations on third states to ensure the implementation of its findings, including that they should not recognize any changes in the physical character or demographic composition of the Occupied Palestinian Territory. It concluded, as it has previously, that all states parties to the Fourth Geneva Convention must cooperate with the United Nations to “put into effect modalities required to ensure an end to Israel’s illegal presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory.”

The raids and displacement at the West Bank refugee camps were occurring while global attention was focused on the devastating hostilities in Gaza, where Israeli authorities have carried out ethnic cleansing, war crimes, crimes against humanity – including forced displacement and extermination – and acts of genocide. Far less attention has been on Israeli authorities’ serious violations of international law in the West Bank. With a new Gaza ceasefire in place and the global focus on avoiding a return to hostilities there, there is a real risk that Israeli authorities will be given more of a free hand in the West Bank to continue targeting refugee camps and escalating grave crimes against Palestinians there. Governments should urgently act to end the forced displacement of Palestinians, ensure their right of return, and prevent further repression of the Palestinian population.

Recommendations

To the Israeli Government

- Immediately stop forcibly displacing Palestinian civilians anywhere in the Occupied Palestinian Territory.

- Publicly declare that all residents of the three refugee camps of Jenin, Tulkarem, and Nur Shams, will immediately be able to return to their homes and places of origin.

- Halt the demolitions and razing and bulldozing of buildings and creation of new roads in all three refugee camps that make permanent changes to the territory.

- Ensure that the humanitarian needs of displaced civilians are met, including food, shelter, and health care, in accordance with the Fourth Geneva Convention.

- Recognize and fulfill the right of Palestinians to return to their homes or areas of origin in the West Bank, other parts of the Occupied Palestinian Territory, or Israel.

- Set up a fair, accessible, independent, and gender-competent mechanism to provide reparation for gross human rights abuses against Palestinians from the refugee camps, including compensation, restitution, justice, and guarantees of non-recurrence. Ensure that victims’ rights are central to the process and victims themselves, including full participation by women, play a key role in designing the process. This should include compensation for any forced displacement or unlawful destruction of property.

- Immediately grant access to the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and Israel, and the special procedures of the UN Human Rights Council.

Accede to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, cooperate fully in the court’s investigations, and cease coercive measures against human rights groups and others advocating for justice before the court.

To All Governments

- Publicly condemn Israel’s forced displacement of the civilian population in Jenin, Nur Shams, and Tulkarem refugee camps as violations of international law by Israeli authorities.

- Urge the Israeli government to immediately halt those violations, allow all Palestinians displaced to return to their homes, and provide them with compensation for damages.

- Cooperate with international judicial bodies and investigative mechanisms investigating the forced displacement at the refugee camps.

- Increase public and private pressure on the Israeli government to stop violating international humanitarian law and international human rights law and fully comply with its obligations and the binding orders and advisory opinions of the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Publicly support and provide funding for UNRWA and oppose the Israeli government’s efforts to restrict its work.

Press the Israeli government to recognize the right of Palestinians, including refugees, to return to their homes.

- Call upon the Israeli government to grant access to independent, international monitors, including the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and Israel and the Special Procedures of the UN Human Rights Council.

Impose targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, against Israeli officials and others credibly implicated in ongoing serious abuses, including Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Minister of Defense Israel Katz, Minister in the Defense Ministry Bezalel Smotrich, and Maj. Gen. Avi Bluth.

Suspend military assistance and arms sales to Israel so long as its forces commit violations of international humanitarian law with impunity.

- Enforce domestic legislation limiting the transfer of arms and military assistance for violations of international human rights and humanitarian law.

- Investigate and appropriately prosecute those credibly implicated in war crimes and crimes against humanity stemming from Israeli authorities’ operations in the West Bank since January 2025, under the principle of universal jurisdiction and in accordance with national laws.

- Suspend preferential trade agreements with Israel as long as the Israeli government refuses to comply with their obligations as lined out in ICJ rulings and advisory opinions and continue to commit serious abuses, including the crimes against humanity of apartheid, persecution and forced displacement, against Palestinians.

Publicly express support for the International Criminal Court, strongly condemning efforts to intimidate or interfere with its work, including coercive measures against court officials and those cooperating with or seeking justice at the court, and committing to support the execution of all its warrants.

Address root causes of grave abuses, including by recognizing Israeli authorities’ crimes of apartheid and persecution against millions of Palestinians.

To the International Criminal Court Office of the Prosecutor

- Investigate as war crimes and the crime against humanity of forcible transfer during Israeli authorities’ forced displacement and other unlawful conduct in operations in the West Bank since January 2025.

- Investigate the individual criminal responsibility or command responsibility of Israeli officials for war crimes and the crime against humanity of forcible transfer.

To UNRWA

- Abolish the discriminatory patrilineal descent requirement for UNRWA refugee status that excludes from refugee registration the descendants of women who qualified or qualify as Palestine refugees under UNRWA’s mandate but whose husbands did not or do not qualify as refugees under UNRWA’s mandate.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews conducted between March and August 2025 with 31 internally displaced Palestinians from Jenin, Tulkarem, and Nur Shams refugee camps in the West Bank between the ages of 16 and 70. Of those interviewed, 20 are women, 10 are men, and one is a 16-year-old girl.

All interviews were either in person in the West Bank in March and June 2025, or by telephone in June and August 2025. Interviews were conducted in Arabic or with interpreters who translated from Arabic to English.

All interviews were conducted in private settings – either alone or with the interviewee’s immediate family members present – with assurances of confidentiality. Researchers informed all interviewees about the purpose and voluntary nature of the interviews, and the ways in which Human Rights Watch would use the information. All were told they could decline to answer questions or could end the interview at any time.

To protect confidentiality, pseudonyms are used for all interviewees except for cases that are already in the public domain. Real names are also used for the documented killings of Ahmed Nimer al-Shaib, Sundos Shalabi, and Rahaf al-Ashqar.

Human Rights Watch was unable to physically access the camps of Jenin, Tulkarem, and Nur Shams because they are closed by the Israeli military. However, researchers spoke to displaced camp residents from Jenin, Tulkarem, and other nearby areas and analyzed dozens of satellite images at different spatial resolutions to assess the scale and patterns of the destruction across the three camps, six months after the beginning of Operation Iron Wall.

To estimate the number of buildings slated for demolition, Human Rights Watch reviewed information included in the Humanitarian Situation Updates issued by the United Nations Office for Coordination and Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and demolition orders posted across social media platforms and likely issued by Israeli military.

To determine locations and to estimate the time and date of specific events that witnesses described occurring during Israeli military raids, demolitions of their homes, or while they were trying to retrieve their belongings, Human Rights Watch matched landmarks in the videos with satellite imagery, street-level photographs, or other visual material and compared with witness accounts.

Human Rights Watch analyzed and verified 31 videos, 27 photographs, and 5 maps posted online; 2 videos and 2 photographs shared with researchers to help corroborate witness accounts and piece together what happened during and after the raids, to identify visible insignia and the types of military equipment used, and to document demolition techniques. Human Rights Watch additionally reviewed approximately 200 videos and photographs posted to Telegram channels used by residents in the camps, and other social media. Where possible, Human Rights Watch used the position of the sun and any resulting shadows visible in videos and photographs to estimate the time of day the content was recorded. Researchers also confirmed that each piece of content had not appeared online prior to the date it was posted, using various reverse search image engines.

Human Rights Watch has adopted specific terminology to distinguish between audiovisual content that we have analyzed and content we have also verified. In the report, Human Rights Watch uses the term “reviewed” for content that has been seen but has not gone through several verification checks. We use the term “analyzed” for content that has been reviewed and appears authentic, but for which we have confirmed some but not all temporal, geographic, or contextual aspects. We use the term “verified” for videos or photographs where we were able to confirm the location, timeframe, and context in which they were taken. We use the term “confirmed” when another individual or organization verified content, which we then checked for accuracy, and confirmed its location, timeframe and context.

Human Rights Watch has preserved the photographs and videos referenced in the report. Where relevant, researchers have included direct links to social media posts in the relevant footnotes. Human Rights Watch chose not to include some links to online content for reasons that included: potential security risks to the people depicted; to avoid sharing dehumanizing representations of people; and that might pose a security risk for the people seen in the content or the person posting it. Researchers also did not include links to content deemed too distressing to maintain the dignity of those shown and minimize readers’ exposure to violent and distressing content.

Background

Israel has been occupying the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip – the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) – since 1967. In 1993 and 1995, the Israeli government and the Palestine Liberation Organization signed the Oslo Accords, which created the Palestinian Authority (PA) to manage some Palestinian affairs in parts of the Occupied Palestinian Territory for a transitional period, not exceeding five years, until the parties forged a permanent status agreement.[3] The Oslo Accords, supplemented by later agreements, divided the West Bank largely into three distinct regions: Area A, where the PA would manage full security and civil affairs, Area B, where the PA would manage civil affairs and Israel would have security control, and Area C, under the exclusive control of Israel. Area A largely incorporates the major Palestinian city centers, Area B, the majority of Palestinian towns and many villages, and Area C, the remaining 60 percent of the West Bank.

The Oslo Accords, though, did not end the occupation in any part of the Occupied Palestinian Territory.

The parties did not reach a final status agreement by 2000, nor did they in the more than two decades since, despite off and on negotiations primarily mediated by the United States. The West Bank remains divided among Areas A, B, and C, with Israel retaining overall principal security control of all areas, and the PA managing some affairs in Areas A and B, which accounts for about 39 percent of the land in the occupied West Bank.[4] Israeli authorities continued to facilitate the expansion of settlements in the occupied West Bank, where more than 730,000 Israelis now reside, in violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention. In the occupied West Bank, Israel subjects Palestinians to draconian military law and enforces segregation, largely prohibiting Palestinians from entering settlements, and severely restricting freedom of movement. This repression of Palestinians in the West Bank is part of the Israeli government’s crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution against Palestinians.[5]

In recent years, Israeli officials have called for the unilateral annexation of additional parts of the West Bank. In May 2025, Israel’s cabinet voted to take sole responsibility for land registration in Area C of the occupied West Bank, a decision that some civil society organizations have described “as effective Israeli annexation of the majority of Palestinian land.”[6] Settlement expansion across the Occupied Palestinian Territory has significantly increased in recent years. In 2025, alone, Israeli authorities had by mid-September advanced plans to build a total of 25,000 housing units in settlements in the West Bank, a record for one year, according to the Israeli group Peace Now.[7]

Refugee Camps

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is mandated by the UN General Assembly to serve “Palestine refugees.” UNRWA sets out that “persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948 and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict,” qualify as refugees under its mandate.[8] It adds that “Palestine refugees, and descendants of Palestine refugee males, including legally adopted children, are eligible to register for UNRWA services.”[9] While they are not registered as Palestinian refugees, the General Assembly has also mandated UNRWA to provide services to “persons in the region who are currently displaced and in serious need of continued assistance as a result of the 1967 and subsequent hostilities.”[10] More than 910,000 UNRWA-registered refugees live in the West Bank, around a quarter of whom live in 19 refugee camps.[11] UNRWA specifically established the three refugee camps covered in this report – Jenin, Tulkarem, and Nur Shams –to house Palestinians who were expelled from their homes or forced to flee during the events surrounding Israel’s creation in 1948 and their descendants.

Since their establishment in the 1950s, the camps have increased in size and density and become marked by overcrowding, forcing the boundaries to expand over the years into neighboring areas.

Over the years, the Israeli military has frequently raided the camps, which have often been a hub for both armed and non-violent resistance to the occupation, and carried out military operations against the fighters they allege are based there.[12] During one 10-day raid of the Jenin refugee camp in April 2002 during the second Intifada, Israeli forces killed scores of Palestinians, some willfully or unlawfully in acts that amounted to war crimes, as Human Rights Watch documented.[13] While camp residents have been forced to relocate as a result of these incursions, for the first time in 2025, the Israeli military has expelled the entire population of the camps, displacing thousands people in the West Bank at a scale not seen since 1967, conducted widespread demolitions, and prevented return.[14]

Escalation of Repression of Palestinians in the West Bank in Recent Years

The raids and forced displacement of refugee camps in early 2025 took place amid escalating Israeli repression of Palestinians in the West Bank. Since March 2022 but particularly since October 2023, Israeli forces have escalated their operations across the West Bank. Since the attacks by Hamas-led Palestinian armed groups on Israel on October 7, 2023, Israeli forces and armed settlers have killed more than 1,000 Palestinians, according to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).[15] Human Rights Watch has repeatedly documented their unlawful use of excessive and lethal force.[16] The number of Palestinians killed the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, in the year after October 7, 2023 was more than in any other year since 2005, when the UN began systematically recording fatalities.[17] UNICEF documented 39 cases of children killed by Israeli forces in the West Bank and East Jerusalem between January and July 2025.[18] Israeli authorities rarely hold accountable, much less prosecute, security force personnel who use excessive force, torture, or commit other abuses against Palestinians.[19]

In addition, Israeli authorities holding Palestinians in administrative detention without trial or charge has in this period reached a 30-year-high.[20] As of November 1, 2025, Israeli authorities held 3,368 Palestinians in administrative detention, as well as 1,205 Palestinians from Gaza under the “Unlawful Combatants” law, a more restrictive form of administrative detention.[21] Additionally, reports have surged of ill-treatment and torture of Palestinian detainees in the West Bank.[22]

Parallel to state violence, Human Rights Watch has documented a sharp spike in settler violence against Palestinians across the West Bank since October 2023, often with the acquiescence or active support of Israeli soldiers.[23] Settlers have attacked Palestinian villagers, burned homes and property, and forcibly displaced dozens of communities. Between October 7, 2023, and April 3, 2024, settler violence displaced Palestinians from twenty communities and entirely uprooted seven communities.[24] During this period, the UN recorded more than 700 settler attacks, with Israeli soldiers in uniform present at nearly half of the attacks. In 2025, settler violence reached an 18-year-high, with more incidents resulting during the first nine months resulting in casualties or property damage (2,660) than in any other since at least 2006, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).[25]

Between October 7, 2023 and September 8, 2025, Palestinian gunmen and unidentified attackers in the West Bank killed 18 Israeli civilians, 13 of them settlers, in addition to 23 members of Israeli security forces, according to OCHA.[26] On January 6, 2025, two Palestinian gunmen shot and killed two Israeli woman, both settlers, and an Israeli police officer near the village of al-Funduq.[27] Israeli forces later killed two men they allege were responsible in Burqin, just over two kilometers southwest of Jenin refugee camp, on January 22, during the large-scale assault on the refugee camp.[28] In another attack, on May 15, 2025, a Palestinian gunman shot and killed a pregnant Israeli woman driving near the settlement of Bruchin in the northern West Bank.[29] Her baby, delivered via Caesarean section, died 15 days later.[30]

“Operation Iron Wall”

Refugee camps that were once full of life…are now reduced to rubble. …This is not just destruction: it is part of systematic forced displacement.

– Roland Friedrich, Director of UNRWA Affairs in the West Bank, June 2025[31]

“Operation Iron Wall,” the name the Israeli government gave to its large-scale military operation in the northern West Bank in 2025, involved the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), Israel Security Agency (Shin Bet), and Border Police. It was intended, in the words of Israeli Defense Minister Israel Katz, to “destroy the infrastructure of terror.”[32] In a February 10, 2025 press release, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) stated:

Palestinian armed groups are also increasingly active in the northern West Bank, deploying improvised explosive devices inside refugee camps, including near UNRWA facilities and civilian infrastructure. They have engaged in violent clashes with both Israeli and Palestinian Forces. From December 2024 onwards, Palestinian Forces operations further exacerbated displacement from Jenin camp.[33]

The campaign first concentrated on Jenin refugee camp in January 2025, but quickly expanded to Tulkarem and Nur Shams refugee camps, and neighboring villages and areas. While the Israeli authorities claimed that the camps were emptied in February 2025, the Israeli military presence remained, causing widespread destruction through the demolition of buildings and preventing return of the camps’ inhabitants. This report focuses on the conduct of the Israeli military and forced displacement from these three refugee camps through July 2025.

The Evacuation Exception

Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention regulates the displacement of civilians in occupied territories, placing restrictions on the forced relocation of individuals by an occupying power during conflicts.[34] A lawful evacuation order is an exception to the general prohibition against the forcible displacement of people from their homes. A military or governmental authority typically issues an order to remove civilians from an area at high risk of fighting or other danger. Such an order can be issued in anticipation of military operations that may last over a more extended period or in response to ongoing or expected hostilities. Lawful evacuation orders aim to safeguard the civilian population by temporarily moving them to safer locations. While article 49 requires the occupying power to return civilians “as soon as hostilities in the area in question have ceased,” the prohibition against forcible displacement under occupation law does not require active hostilities. The prohibition applies for the entire duration of the occupation, even when no fighting is occurring.[35]

In Gaza, the Israeli military stated that it was using a range of methods to evacuate the population safely. But Human Rights Watch found no plausible imperative military reason to justify the mass displacement of the population and that these actions amounted to war crimes and the crime against humanity of forced displacement.[36] In the northern West Bank, the Israeli military failed to implement any form of organized evacuation system that would have allowed residents of all three camps to leave safely. The Israeli military has at times claimed that it was not forcing the population of the refugee camps to evacuate, and at others claimed the opposite: amidst the Jenin raids, the Israeli military said it was “enabling any resident who chooses to exit from the area to do so via secure and organised routes with the protection of Israeli security forces.”[37]

Human Rights Watch found that the military entered and stormed each of the three camps without prior evacuation orders, conducting military operations while simultaneously forcing civilians to flee. In February 2025, Israeli Minister of Defense Israel Katz said, “I instructed the IDF to prepare for a long stay in the camps that were cleared, for the coming year, and not allow residents to return.”[38]

Jenin Raid

In December 2024, the Palestinian Authority (PA) conducted a large-scale security campaign called “Protect the Homeland.” It targeted “outlaws and militants” with the aim of restoring “law and order” in Jenin refugee camp and the city of Jenin. From mid-December 2024 to January 20, 2025, the PA conducted operations in the camp – raiding homes and mosques, resulting in arrests and a number of deaths, including security officers, at least two children, a journalism student, and an unarmed resident riding a motorcycle, according to the Palestinian statutory body, the Independent Commission for Human Rights.[39] Residents said that, beginning in December 2024, confrontations between PA forces and fighters in the camp led to severe damage to electricity cables and water tanks on the roofs and the cutting off of essential services, including electricity, water, and access to food. That same day, trucks began dumping mounds of dirt, blocking entry or exit from the camp.[40]

PA forces appear to have left the camp on or before January 21,[41] hours before the commencement of Israel’s Iron Wall military operation. Operation Iron Wall officially began on January 21, just two days after a ceasefire between Palestinian armed groups and the Israeli military took effect in Gaza on January 19, 2025.[42] It involved ground troops, aerial fire from Apache helicopters, drones, armored vehicles, and bulldozers.[43]

The Israeli military said it was operating in Jenin to target alleged Palestinian militants in the refugee camp, with the Israeli military spokesperson Lt. Col. Nadav Shoshani telling reporters in a briefing that the operation was intended to prevent militants “from regrouping” and attacking Israeli civilians.[44]

Fatima B., 44, said that on January 21 she was with her husband and four children at home in the central al-Hawasheen neighborhood in the center of Jenin camp when the Israeli military raid started:

It was around noon, and I heard the sound of an aircraft and it sounded like it was shooting at people. … At first, we hid inside the house – we didn’t know what was happening, we stayed hidden for maybe five to ten minutes, but then we heard people outside shouting, saying we should leave.[45]

A video posted at 12:33 p.m. to a Telegram channel used by Jenin refugee camp residents shows a siren blaring from a mosque in Jenin camp. Aircraft can be heard in the air.[46] Another video, posted in a different Telegram group used by camp residents, at 12:52 p.m. and analyzed by Human Rights Watch, shows an Apache attack helicopter firing its cannon in the air, reportedly over Jenin camp.[47] A helicopter can also be heard firing in a video posted at 12:54 p.m. and verified by Human Rights Watch showing family homes and the hills flanking Jenin camp.[48]

Fatima B. and her family fled their home immediately, taking nothing with them.

They followed camp residents who said that announcements had been made via drones flying overhead directing them to leave the camp through Awdeh roundabout. The roundabout was the location of a major intersection on the camp’s northwestern edge that Israeli forces had bulldozed months earlier: Fatima B. said:

The drones came at the same time as the airplane. I couldn’t exactly make out what the drones were saying but other people told me they were saying to leave. It was so scary – we didn’t look up – we heard the sound of the airplane and the sound of the drones, we had our kids with us, we just rushed and were running and trying to take care of our kids.[49]

Fatima B. and her family exited the camp through Awdeh roundabout, where she said Israeli soldiers, had set up an informal checkpoint to run security checks on people as they were leaving. Human Rights Watch verified a video taken in Awdeh roundabout and shared on social media on January 22 showing what Fatima described.[50]

At about the same time Fatima B. was leaving the camp, a silver Kia passenger car carrying fleeing people, including a child, was shot at about 200 meters west of the Awdeh roundabout, as it was traveling in a westward direction away from the camp. A video posted to social media that same day, filmed from inside the vehicle – whose dashboard clock read 1:10 p.m. – showed a man driving with women and a little boy. Multiple shots ring out as the little boy shouts, “Go, go!” in Arabic, and a woman starts praying. She screams, “Oh, God!” before the car swerves and the video cuts out.[51] A second video, filmed from outside the vehicle and shared on social media, shows the Kia speeding along the road before abruptly stopping.[52] A third video, posted to Telegram at 1:47 p.m., shows a silver Kia crashed into the side of the road, its doors ajar, and apparent small caliber bullet holes in the windshield. An Israeli military vehicle is visible behind the vehicle as the sound of drones buzz overhead.[53]

Human Rights Watch verified and geolocated the three videos. The car crashed into a curb on Balat al-Shuhada Street, less than 400 meters from the roundabout. Social media and news reports said the driver, Ahmed Nimer al-Shaib, a resident of Burqin, just southwest of Jenin camp, died trying to flee after picking up his son from school.[54]

Within hours of the raid beginning, Israeli military bulldozers rolled through Jenin,[55] and began ripping up roads leading to the camp.[56]

Anoud C., a 36-year-old who was undergoing intensive treatment for lung cancer, was at home in the center of Jenin camp with her sisters and their children when the raid began:

It was around noon. ... First, I heard the helicopter, and when we were leaving the house, I saw an Apache [helicopter]. I could hear explosions, there were four explosions first, before the helicopter began to shoot over our heads and at the people.

I was terrified and scared. We were panicking, it all happened so fast. Out of fear we had to leave.[57]

Anoud C. with her family fled their house, between al-Damaj, al-Hawasheen, and Faloujeh neighborhoods, holding a white cloth. “We were frightened,” she said. “We didn’t know what to do, we just left the house without anyone asking us to leave.”[58] She described the scenes of panic and chaos as she and other camp residents tried to escape the violence:

I was not able to take anything with me – just my ID and my purse. When we fled, we saw many people, many camp residents. We saw dead people on the ground. …The soldiers were wearing different uniforms. When we left the house, near the hospital, we saw tanks and military cars in front of us, rushing into the camp. We stepped aside until they passed us.[59]

Anoud C. sought refuge with her family at the premises of the Society for the Blind, an organization that provides essential services to children and youth who have visual disabilities situated on the southern entrance of Jenin city.

While many families fled their homes in Jenin camp on the first day of the Israeli raid, other camp residents stayed in their homes until Israeli drones with loudspeakers told them to leave.[60] Sara D., a 65-year-old Jenin camp resident, described what she heard on January 22:

On the second day [of the raid], drones started circulating the camp and ordered people to leave. I didn’t see the drone [that had the loudspeaker], but I heard it – it was ordering us to leave the camp between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. and to go through the Awdeh roundabout. It was saying in Arabic: “Evacuate your home, if you don’t, you will bear the responsibility, we will destroy the camp.” The drone would come to the window and circle around the area, repeating the sentence over again.[61]

She felt confident that the order was coming from the drone, not Israel soldiers nearby:

I’m sure it was a drone because the sound came from high up, it wasn’t from a military jeep on the ground. I told my sister-in-law [with me in the house], there’s no chance for us to stay and that we had to leave.[62]

Sara D. fled her home with her sister-in-law and her children, including her adult nephew who uses a wheelchair. She described their flight:

We thought it would be one or two days and then we would come back to the camp and our home. We left with the clothes on us, nothing else, not even my medicine. The situation was very difficult. …When you have kids and a person with a disability, you only think about them and their safety. Even when we were leaving and heading towards the Awdeh roundabout, the Israeli soldiers [near us] started shooting in the air, I think, to scare us, but we continued walking until we reached the Awdeh roundabout.[63]

Residents said that they could see drones following and tracking their movements as they fled towards the roundabout.[64] Sara D. said:

[The Awdeh roundabout] was filled with soldiers, and the Israeli military had set up a checkpoint. I could only cross through it after looking into a camera that scanned my eyes. Soldiers told people to look into the camera and after the scan I saw some people were taken aside.[65]

Human Rights Watch verified a photograph posted to social media and published by Al Jazeera on January 22 showing dozens of men, women, and children gathered on foot at the Awdeh roundabout and walking westward on the ripped-up Balat al-Shuhada Street along the Wadi Burqin corridor.[66] Photographs taken by an Anadolu Agency photographer and published online on January 23, and verified by Human Rights Watch, show dozens of men, women, children, and older people, including people with disabilities, walking along this same destroyed road, many of them struggling while carrying plastic bags or luggage with possessions.[67] One photograph, taken 100 meters from where Ahmed Nimer al-Shaib was killed in his car, on the same route he took on January 21, shows three women, arm in arm, one of them an older woman hunched over and gripping a cane, as they walk westward from the Awdeh roundabout.

Sara D.’s family found shelter at the same Society for the Blind school that housed Anoud C. and other displaced families.

The Israeli military systematically expelled the entire population of Jenin refugee camp. Since then, Israeli forces have installed sandbags and military gates at camp entrances, blocking residents from entering.[68] They patrol in armored vehicles, have bulldozed roads and damaged and demolished infrastructure, converted residential homes into military posts, and hung Israeli flags from some buildings.[69]

Tulkarem Camp Raid

After Israeli military forces raided Jenin, it expanded its campaign to Tulkarem refugee camp on January 27. The Israeli military employed tactics similar to those used in the Jenin raids, deploying ground troops, drones, tanks, and bulldozers to clear the camp of its residents.[70]

On the morning of January 27, residents posted reports of reconnaissance aircraft over Tulkarem camp on Telegram. Leila E., a 54-year-old social worker, was in her home that morning in the northeastern part of the camp, on al-Shahid Taleb Sarouji Street, al-Balawneh neighborhood, with her children and grandchildren, when Israeli military forces entered her street:

It was around noon and we were cooking. … We knew the Israeli military would be coming. … [W]e followed the news on a Telegram channel. … They [the Israeli soldiers] kicked the door and entered – it was about 25 soldiers with a dog – it was terrifying. It was like another Nakba.[71]

Leila E. described how the Israeli soldiers forced her and her family from their home:

They [Israeli soldiers] were screaming and throwing things everywhere.... No one explained anything, they were just destroying the house, screaming and using bad words. It was like a movie scene – some had masks and they were carrying all kinds of weapons. I could see grenades, and they had big machine guns. ... The soldiers pushed us outside the house. ... [T]hey screamed at us to leave the house. ... One of my girls explained to the soldiers that she needed to get milk and clothes for the kids, but one of the soldiers said, “You don’t have a house here anymore. You need to leave.”[72]

Once on the street outside her home, Leila E. said she saw Israeli soldiers using two bulldozers. She identified one as an Israeli military Caterpillar D9 bulldozer, and the other she said was used to remove rubble and place it on the side of the road. Her area had already been partially bulldozed weeks earlier.[73]

Leila E. said that in their rush, her daughter, who was four months pregnant at the time, fell over. She subsequently experienced a miscarriage, an event Leila said she was still mourning when we spoke with her in late March.

By 5 p.m., Israeli forces had stormed the camp from most entrances. Residents updated one another on Telegram in real time, posting photographs and videos later verified by Human Rights Watch.[74] These include videos showing Israeli soldiers on foot outside of al-Zakat Hospital, southwest of the camp;[75] a bulldozer ripping up Jamal Abdel Nasser Square leading to the camp, also to the southwest;[76] military vehicles driving past Tulkarem Governmental Hospital, north of the camp;[77] and a convoy with a bulldozer driving past Palestine Technical University-Kadoorie, to the west of the camp.[78]

Leila E. said the Israeli soldiers did not tell them where to go, and when she asked, the soldiers just repeated that they should leave. She and her family made their way on foot east from al-Balawneh, now largely destroyed, to another daughter’s home in the nearby village of Dhennaba, in between Tulkarem camp and Nur Shams camp.[79]

As of the end of July 2025, Leila E.’s house was still standing. The row of buildings adjacent to her house were slated for demolition as part of a demolition order issued on May 1. Satellite imagery analysis shows that the street where Leila’s house is located has been widened and the destruction caused by the operation expanded to both sides of the street. Human Rights Watch verified a video shared with researchers showing heavy damage to Leila’s house along with surrounding buildings.

By the morning of January 28, the main entrance leading to the camp on Nablus Road was torn up, with a gaping crater in the ground in place of pavement, along with other landmarks in and around the camp.[80]

Some residents said they were forced to leave their homes several days after the raids on Tulkarem began. They said that Israeli military forces were clearing people from the camp, area by area, during that time. “They [Israeli soldiers] came to the street on February 1 at 11 a.m. and started shooting,” said Yusuf F., a 40-year-old man from Tulkarem refugee camp who uses a wheelchair.[81] He said he was terrified, and together with the rest of his family – some 20 members – gathered on the ground floor of the three-story building where they were living on Schools Street in the northwest of Tulkarem camp:

The Israeli soldiers were shooting everywhere, the bullets were entering the walls and doors around us. …They were screaming, and using bad words. … After the shooting stopped, they ordered us to go outside. They split up the men and women and put all the men against a wall for 30 minutes and made us take off all our clothes and strip-searched us. I am paralyzed, so my brother had to help me. Then they ordered us to leave.[82]

Yusuf F. said that the soldiers would not let him take his electric wheelchair, allowing him only to bring his manual wheelchair with him, which he is not comfortable using.[83] The bulldozed street and surrounding area, which was no longer paved, instead was now a dirt path with mounds of earth on either side, making it difficult to navigate for people who use assistive devices such as wheelchairs and walkers.

People with physical disabilities had to rely on family and neighbors to assist them through streets damaged by Israeli bulldozers, or to physically carry them to safety. In a video and series of photographs posted on Telegram on January 28 and verified by Human Rights Watch, at least seven older people with mobility aids and assistive devices can be seen struggling to exit the camp, making their way past mounds of earth and jagged metal where buildings once stood. Drones are audible in the video. In one photograph, a shoeless older man in a mud-caked wheelchair sits on the side of a destroyed road.[84]

Yusuf F. said:

The street is not easy for me to use without my electric wheelchair. ... So my neighbor picked me up and carried me out of the street… When the Israeli soldiers told us to leave the area… a lot of people were asking where we should go, and when could we come back, but the soldiers didn’t answer. The only instruction they gave us was to leave the camp from near the school and then leave the area and don’t come back. ... There were a lot of drones in the sky that day – we could see them clearly.[85]

Yusuf F. and his family sought shelter in a small sports club outside the camp. He then moved to a school where he used to work before taking out a loan to rent a place where he and his wife could live.

By late March 2025, all the residents of Tulkarem camp had been forced to nearby areas, leaving the camp empty. Its entrances were sealed, and soldiers patrolled with military vehicles and raised Israeli flags outside of some buildings in the refugee camp.[86]

Nur Shams Camp Raid

On February 9, Israeli military forces began operations against Nur Shams refugee camp, which lies east of Tulkarem camp and along the main road that connects Tulkarem to the city of Nablus.[87]

Israel military forces, in operations similar to those used to empty Tulkarem camp, entered Nur Shams area by area, forcing residents to leave, using military vehicles, drones and ground forces.

Just before 2 a.m. on February 9, and later in the morning, reports surfaced on local Telegram groups of reconnaissance drones above the camp, Israeli military vehicles spotted in numerous neighborhoods, and subsequent raids on homes.[88]

A video posted to Telegram at 4:54 a.m. that morning and analyzed by Human Rights Watch shows women, men, and small children walking past one of the many greenhouses in the south of the camp, on a pitch-black road.[89] “They didn’t allow us to go through there [a road leading to a mosque in Tulkarem]; they sent us through Kafr al-Labad Road,” says one of the men, holding a child’s hand, referring to a road running east of the camp.[90]

Nadine G., a 53-year-old woman who used to manage a center for people with disabilities in Nur Shams, was in her house with her husband and 14-year-old daughter in the “Schools neighborhood” on the southern edge of the camp when the raids began early on February 9:

I saw on the Telegram news channel that the Israeli military had started storming Nur Shams. That’s how I first learned that the raids here had started. One hour after this, the soldiers were in front of my house. I started to hear the sounds of bulldozers and “tiger jeeps,” a kind of military jeep.[91]

Nadine G. said she then heard bullets around her house. She read reports on social media that Israeli forces had shot and killed her neighbor, Sundos Shalabi, 23, who was eight-months’ pregnant at the time. Social media reported that Israeli forces killed Shalabi in the early morning as she fled their neighborhood by car.

Human Rights Watch geolocated a photograph of Shalabi’s gravely injured husband[92] in a car next to a greenhouse about 200 meters south of the “Schools neighborhood,” in addition to another image shared on social media showing a different angle of the car around sunrise.[93] Shalabi‘s husband, Yazan, survived with life-altering injuries that led to a disability including partial paralysis, requiring him to use a wheelchair. Researchers geolocated an image of Shalabi’s body slumped on the ground close to the car.[94]

An investigation by the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem quoted Bilal Abu Shu’lah, Shalabi’s 19-year-old brother-in-law who was with her just before her killing. “The last time I saw her, when we were near the car and the [Israeli] soldiers took me, she wasn’t injured at all,” he said.[95]

Shalabi had called her father-in-law’s cell phone around 3:30 a.m. that morning in distress, according to Shalabi’s mother-in-law, Umm Bilal.[96]

“[My husband] put her on loudspeaker, and I told her to knock on doors and see who could help,” Shalabi’s mother-in-law told Human Rights Watch. “I was on the phone with her calming her down, she told me not to leave her alone. I even heard her knocking on the door while on the phone with me. …She kept telling me, ‘Don’t leave me,’ and telling me she saw Yazan bleeding. Then suddenly we heard a gasp. Sundos said, ‘Akh, akh,’ twice. Then she went silent.”[97]

A report by the Israeli newspaper Haaretz that cited a preliminary Israeli military investigation reported that Shalabi was unarmed, saying she had “looked suspiciously at the ground” and was “shot three times in the chest.”[98]

Human Rights Watch analyzed hospital autopsy and medical reports, which said Shalabi was shot in the back and pelvis, killing her and her fetus, as well as CT scans that clearly show the trajectory of the bullets. According to the Independent Forensic Expert Group, which was consulted by Human Rights Watch and reviewed the hospital reports and CT scans of her wounds, Shalabi was shot at least twice, with the bullets striking her in the upper back and the back pelvis region, shattering her spine.[99]

In response to questions about the killing of Shalabi, the Israeli military’s International Press Desk said:

[A] Military Police investigation has been opened. Upon its completion, the findings will be transferred to the Military Advocate General’s Office for review. Naturally, we cannot provide details on an ongoing investigation.[100]

Just over 200 meters to the north, Nadine G. hid with her husband and daughter in her daughter’s room for 72 hours:

I could see the Israeli soldiers and two bulldozers, D9 bulldozers, destroying the wall of my garden while we were hiding. There were drones circling – we could hear the sounds of destruction. We stayed three days inside that room and we were so scared. I didn’t want to leave. We didn’t have electricity... and the soldiers never tried to communicate with us.[101]

At 6 a.m. on February 9, Medina TV posted on Facebook saying that the Israeli military had forced camp residents of nearby Jabal Saleheen, a neighborhood on the eastern edge of the camp, out of their homes, and turned them into military barracks.[102] Israeli military bulldozers and excavators tore through the camp: A video posted to X on February 10 and verified by Human Rights Watch shows D9 bulldozers ripping through a street in Jabal Saleheen, destroying a house’s wall and flipping a car.[103]

Nadine G. said she eventually left her house when one of her neighbors came to tell her that the soldiers had ordered people to leave the camp. She packed three bags for her and her family and followed the directions of the Israeli soldiers who were outside her house:

The soldiers told us to use a particular road to exit the camp. I couldn't recognize the camp… the houses had been destroyed, and there were destroyed cables. There was fuel mixed with water on the ground and we were forced to walk on this. There were more than 40 men, and maybe 45 women with their children walking with us at the same time from my neighborhood. As we were walking, drones were following us overhead and there were maybe 20 to 25 soldiers, aiming guns at us. They were wearing dark green uniforms. They were telling us which route to take. We were meeting women along the way who had also been forced to leave and they were all crying.[104]

Once she reached the main entrance of the camp, Nadine G. said that Israeli soldiers had taken over a building and installed a makeshift checkpoint and were checking people’s IDs as they left the camp. The soldiers checked her ID and allowed her and her daughter to leave but detained her 75-year-old husband for a few hours before releasing him. She said she found shelter in a hotel run by relatives sharing one room with her husband and daughter. “All my dreams have been erased,” she said.[105]

Nour H., a 36-year-old woman with five children, was at home with her family in the Mansheeya neighborhood, in the northeast of Nur Shams camp, on February 9 when the raids began:

I knew on February 9 that the raid on Nur Shams had begun, as I was following the news on social media. In the early hours of February 10, we didn’t have internet anymore to check the news, but I could hear the bulldozers and I could hear their [Israeli soldiers’] voices yelling and I could hear the sounds of destruction. At 6 a.m., the Israeli military started shooting at our house wall, and at 7:30 a.m. a drone smashed through one of the windows and the kids started crying. Then an Israeli soldier told my brother who was living on the first floor to gather everyone in the building on the first floor. All of the Israeli soldiers were holding weapons and there were more than 100 of them there throughout the building.[106]

Nour H. said that the Israeli soldiers took her brother-in-law away and she suspected that he would be detained but later found out that he had been ordered to go to other homes and instruct people to leave the camp[107] – actions that may amount to using a civilian as a human shield. “Human shielding” is purposefully using the presence of civilians to shield military objectives or operations from attack, and is a violation of the laws of war and constitutes a war crime.[108] Nour H. said that she and 17 relatives spent approximately 11 hours waiting in one room of their home under Israeli instructions. After 11 hours, her brother-in-law returned and said they had 10 minutes to leave the camp:

I asked the soldiers where we should go and they said to the east, and they told us if you go to the left or to the right you will be targeted by snipers who are in high places around the area. When we left, there was a drone above us and it followed us from Malabe neighborhood to Ghazal mall, all the way.[109]

Nour H. fled east with her family to her parents’ house outside the camp area.

Abdallah al-Ashqar, a 51-year-old father of seven, was at home with his family on February 9, just next door to the UNRWA Nur Shams Boys’ School, in the “Schools neighborhood,” when he heard that Israeli military forces had started to raid the camp. Al-Ashqar had been following the news on Telegram, and at 3 a.m. he learned that Israeli forces were in Dhennaba village between Tulkarem camp and Nur Shams. He had seen Telegram posts from people saying they expected Nur Shams would be raided next. His family prepared themselves and made sure they had their IDs and documentation with them. At 10:30 a.m. that day, his 21-year-old daughter, Rahaf, said that she could see soldiers encircling their home. Al-Ashqar said Rahaf went back and forth between the windows in different bedrooms and the main entrance describing what the soldiers were doing:

After this all back and forth, she went to the main door in the house and she said, “Dad, our garden door is open.” She pointed to two poles around the house with wires around them, and said it looked like the Israeli soldiers were setting up to bomb something. When Rahaf was showing me this, she was on top of the couch, and then the bombing happened. …The soldiers blew up the door. …

I was closer to the door than Rahaf – she jumped and then was in front of me. I was looking at Rahaf and I saw a white spark, and there was a big loud boom. Rahaf was pushed right back and fell to the floor and shouted, “Help me.” I was crawling to her, and I heard her take her last breath. Her mum screamed.

They could have warned us, with speakers or something... but they didn’t do anything.[110]

Rahaf died in the attack. Al-Ashqar suffered injuries in his legs from shrapnel: “There was broken metal and glass everywhere.”[111] He said that the soldiers then entered his home:

I had been thrown to the ground and then two soldiers broke into the house. They checked Rahaf’s pulse to see if she was breathing and that was it. They ignored me, even as I was bleeding. …

After a while, many soldiers came, maybe dozens, and they were asking, “Where are the weapons?” I was looking at them, ransacking our rooms, our washing machine, all our clothes.[112]

In response to Human Rights Watch questions regarding the killing of Rahaf during the attack, the Israeli military’s International Press Desk said:

In connection with the case of Rahaf al-Ashkar, forces were preparing to arrest a wanted terrorist known to the security system and residing in Nur al-Shams, within the jurisdiction of the Ephraim Brigade.

The forces called on the residents of the house to come out in order to arrest the suspect. When they did not respond, the forces were compelled to breach the door using explosives. As a result of the breach, a woman in the house was injured. The forces coordinated the rapid arrival of the Red Crescent to treat her.[113]